Slide attacks

Earlier we discussed the situation where we use one round key for the first half of the cipher, and a different key for the second half. This setup allowed us to attack the cipher from "both sides". But what if we used the keys in an alternating fashion instead? Rather than using them for the first and second halves, we could use the keys one after the other like so:

def random_roundkey(bits: int):

t = randint(0, 2**bits)

return int(sha256(str(t).encode()).hexdigest()[:16], 16)

a, b = random_roundkey(BITS), random_roundkey(BITS)

cipher = Present(rounds=32, custom_roundkeys=[a, b] * 16)

Surprisingly, this proves not much safer, though for reasons that may not be immediately obvious. Before we dive into that, let's look at a simpler example:

def random_roundkey(bits: int):

t = randint(0, 2**bits)

return int(sha256(str(t).encode()).hexdigest()[:16], 16)

a = random_roundkey(BITS)

cipher = Present(rounds=32, custom_roundkeys=[a] * 32)

Till now, the best way we've seen to attack the cipher in such a setting has been brute forcing the round key as we did in 02 - Brute Force. This works well when the round key is small, say 32-bits or less, but a PRESENT round key is traditionally 64-bit. A natural question is whether there's a more clever way of abusing the lack of round key variety.

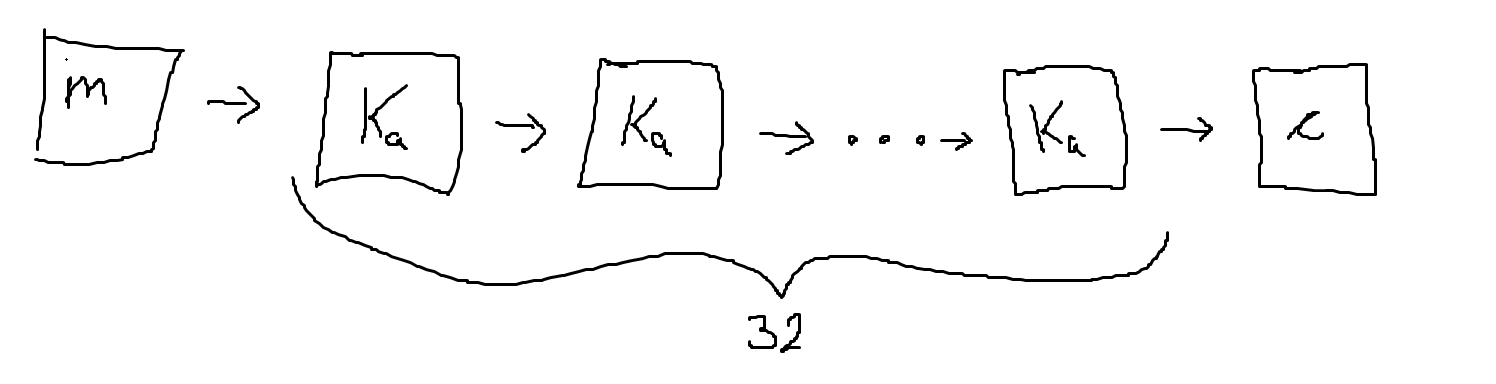

Visualising PRESENT

In 03 - MITM we split up the cipher into each of its rounds.

For a message $m$, after applying the 32 rounds of the cipher, we get a ciphertext $c$. Notice how each round is effectively the same function $f$ being applied consecutively. That is, $f^{32} (m) = c$.

Slid pairs

The block size of PRESENT is 64 bits. That is, both $m$ and $c$ are 64-bit values. Suppose we encrypt a large amount of messages. Then, by the birthday problem1, we expect that after $2^{32}$ encryptions at least two of these ciphertexts should match. A similar argument tells us that we can expect to find two pairs $m_1$ and $m_2$ such that $c_2 = f(c_1)$. Were we to find such a pair (called a slid pair), we could attempt to find the round key — attacking just one round is much easier than thirty-two!

Earlier, we discussed what goes into a single round of PRESENT: key addition, substitution, and permutation. Out of these three operations, only the first is key dependent, meaning that the others can be inverted without knowing the key. This reduces process of finding the round key to a simple XOR operation!

Task 1 The following was encrypted with one round of PRESENT:

m = 0x14214213

c = 0x23123213

Determine the key.

In practice

Obviously, we can't check whether $c_2 = f(c_1)$ by just applying $f$ to ciphertexts because we don't know the round key. Instead, for every candidate slid pair (i.e. every pair), we attempt to recover the round key. Then we verify whether $f^{32}(m_1) = c_1$ for our recovered round key. If so, we've recovered the right one.

The other thing to note is that thus far we've been ignoring the last round of PRESENT; that is, we've been treating it as being no different than any other. Surprisingly, this isn't too much of a problem. As the last round is only missing the substitution and permutation steps, we can apply those two ourselves, and then continue with the assumption that all rounds are equal.

It's important to note that slide attacks are rather memory intensive. We need to store a lot of plaintext-ciphertext pairs. For a 64-bit blocksize, we anticipate $\approx 2^{32}$ blocks being needed, which comes out to about 34 gigabytes of storage. For larger block sizes, this quickly grows impractical as an approach.

The Slide Attack

Now it's your turn to implement the attack. The Wikipedia article may prove helpful.

Task 2 For the following slid pair, determine the key and decrypt the ciphertext

0x124324.

m1 = 0x123

c1 = 0x123

m2 = 0x123

c2 = 0x123

Task 3 Given the attached files, decrypt the ciphertext

0x123.

plaintext.txtciphertext.txt

-

The birthday problem, in the context of block collisions, tells us that for a $n$-bit blocksize we may expect a collision after $\frac{n}{2}$ blocks. ↩