Linear trails

Thus far, we've kept using bias (and correlation). It may seem tempting to rely on probabilities when discussing approximations. However, this has a few shortcomings which we will now go over, and improve upon.

Distinguishers

Much like with differential cryptanalysis, the focus of our attacks is on preparing distinguishers — that is, a way to differentiate a cipher's output from random output. This is actually what we've been buildings towards this entire section. By using and verifying our approximations, we can tell whether we're dealing with a biased output quite easily. The only question that remains is how to do so efficiently.

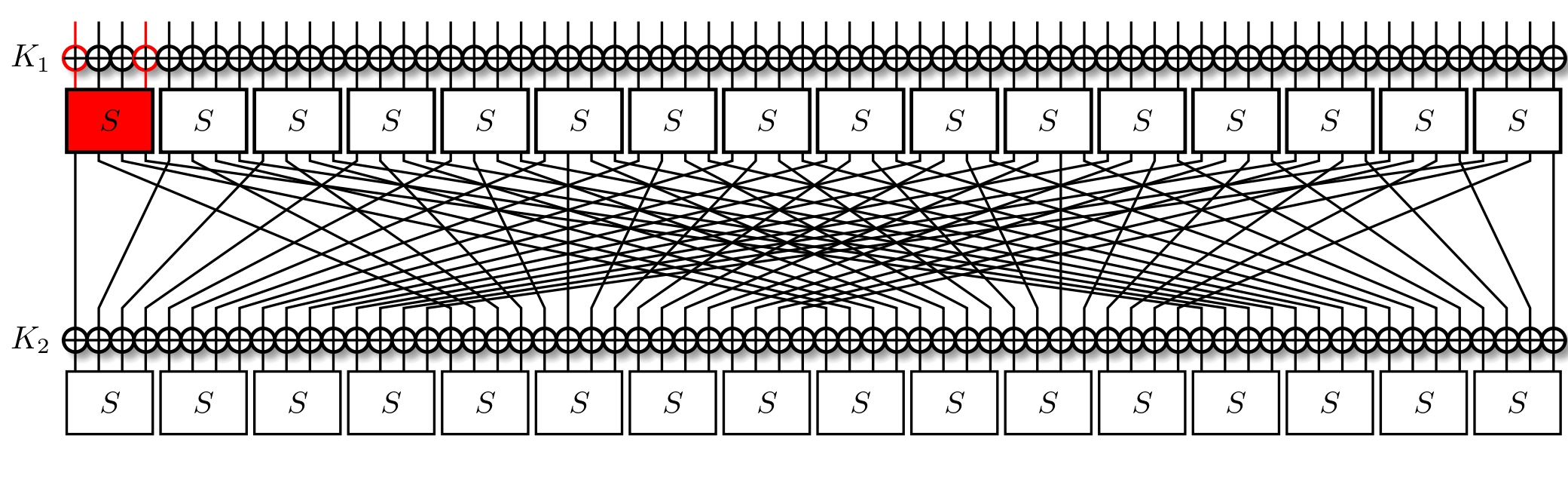

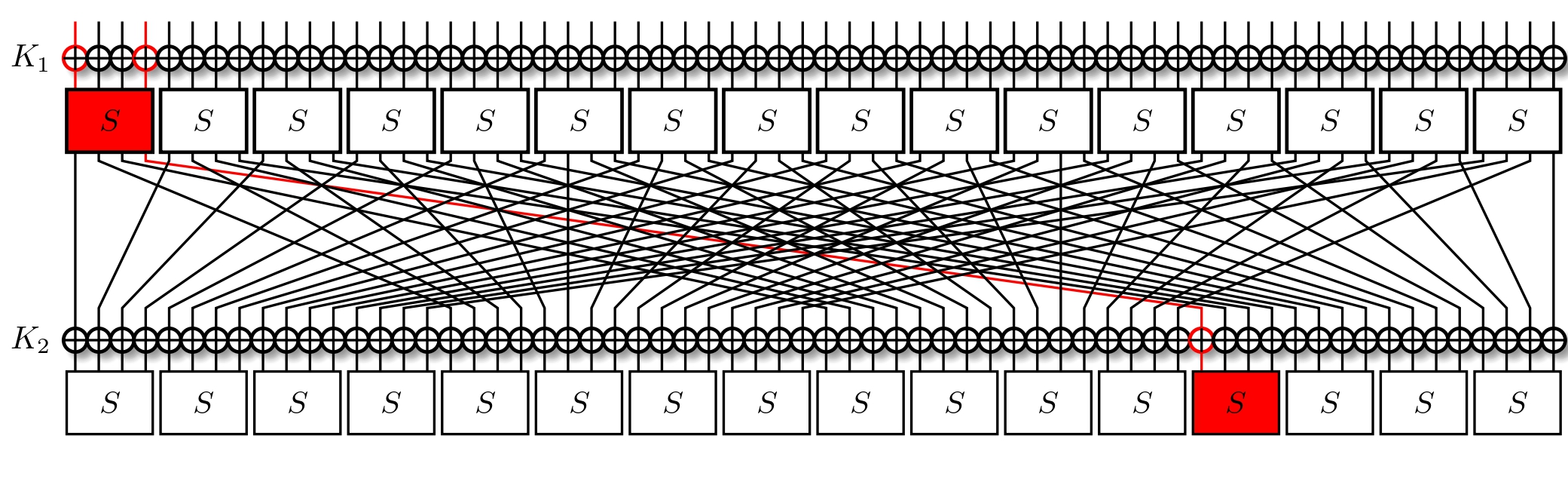

Let's tackle the PRESENT cipher again, specifically its first round. We'll pick out some initial mask $\alpha = 9$ for the input of the top-most S-Box. The XOR is linear, and so doesn't change what bits we're observing.

We now check the LAT, and see which output masks have with a bias. We take $\beta = 1$ as our example; it holds for $\text{LAT}[\alpha][\beta] = 4$ inputs more than expected, so with a probability of $p_1 = \frac{12}{16}$ and with a bias of $\epsilon_1 = p - \frac{1}{2} = \frac{1}{4} = 2^{-2}$ ($\textbf{corr}_1 = 2^{-1}$). For one round, this is simple to calculate and use: we have the expected probability right there. But how does the situation evolve when we go for a second round?

The chosen output mask results in one active bit. We follow this bit through the permutation layer, and find it ending up in another S-Box.

This time around, we have $\alpha = 8$, so we consult our LAT. A strong approximation would be $\beta = \text{0xe}$, holding in $\text{LAT}[\alpha][\beta] = 4$ inputs more than were it a random approximation. So it holds with probability $p_2 = \frac{12}{16}$ and a bias of $\epsilon_2 = p - \frac{1}{2} = 2^{-2}$ ($\textbf{corr}_2 = 2^{-1}$).

How do we know the overall, 2-round probability? One idea may be to simply multiply the probabilities. After all, it is what we did for differential trails. However, this doesn't really work, and it may not be obvious why not either.

Issues with probability

Starting off, the two approximations we made are not independent events, meaning that they cannot be multiplied so simply. In fact, even the first substitution is not quite what we make it out to be. While we easily ignored the round-key additions during differentials, we cannot do so for linear approximations. If a key-bit is 0, the bias remains the same. If a key bit is 1, it changes its sign. Meaning that the probability that it holds flips just as well.

This can also be seen from our earlier definition of the solution space: $$ s = #{x\ |\ \alpha \cdot x = \beta \cdot f(x) } $$ Accounting for key-addition, we have that: $$ s = #{x\ |\ \alpha \cdot (x \oplus k) = \beta \cdot f(x) } $$ Since we only care about the inner product, a single bit change also changes when we have an equality.

This all implies that any key-addition affects the probability. However, it doesn't impact the bias that much- more specifically, it doesn't impact the magnitude of it, only the sign. This is why we introduced and use bias and correlation; they remains relevant round after round.

Piling-up lemma

As it turns out, we have a nice instrument by which we can combine multiple consecutive approximations. We state the following lemma:

Piling-Up Lemma: Suppose $T_i$ are independent discrete random variables with correlations $\textbf{corr}_j$, $j=1,2,\ldots,k$. Then the correlation $\textbf{corr}$ of $T = T_1 \oplus T_2 \oplus \ldots T_k$ can be calculated as $$ \textbf{corr} = \textbf{corr}_1 \textbf{corr}_2 \cdots\textbf{corr}_k$$

The above can be restated with bias as well, but is less clear. The proof for the lemma is usually done via induction and using biases, and we omit it for brevity, but it can be found in e.g. these slides.

The impact of the lemma is that we can simply multiply the correlations to get our total correlation. This is much simpler to work with, and what we'll be going with forwards. In the next section, we'll look at extending this trail further, and then using it to attack the cipher.