Approximations in practice

Enough theory. Let's get our hands dirty.

Extending the trail

We'd looked over a two-round trail on PRESENT, but we didn't properly try to exploit it. Recall that the an advantage of linear cryptanalysis is that we aren't reliant on choosing our messages, and are operating in a known-plaintext model.

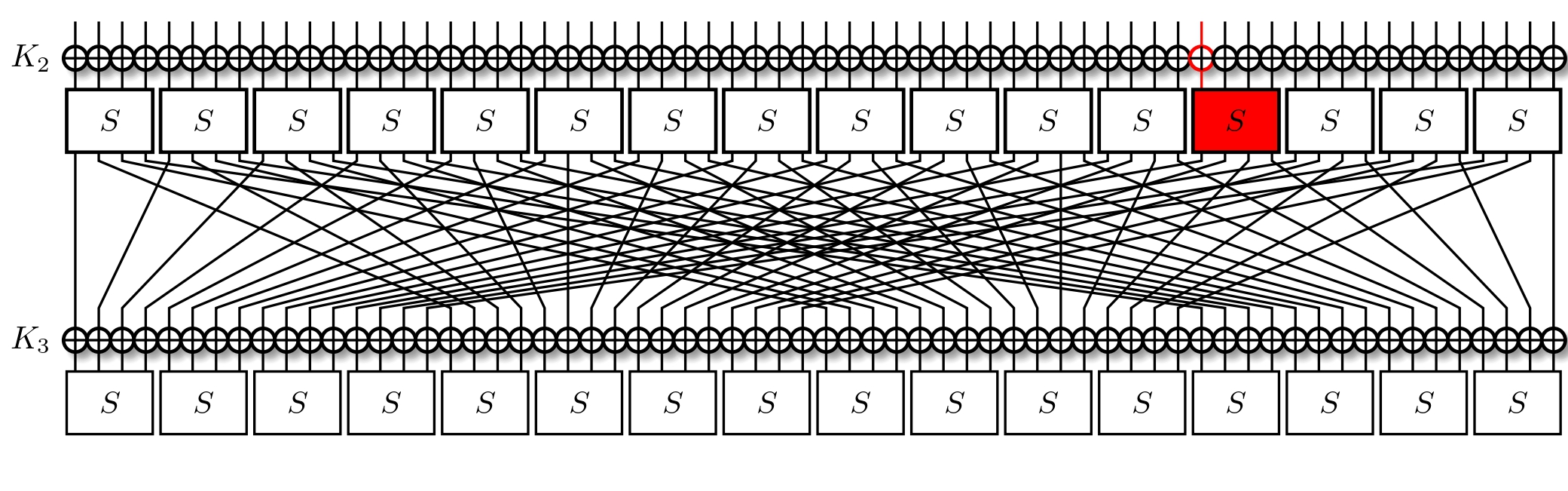

Our two-round approximation was $\text{0x9} \ll 60 \rightarrow \text{0x8} \ll 12$, meaning we're currently at the following step:

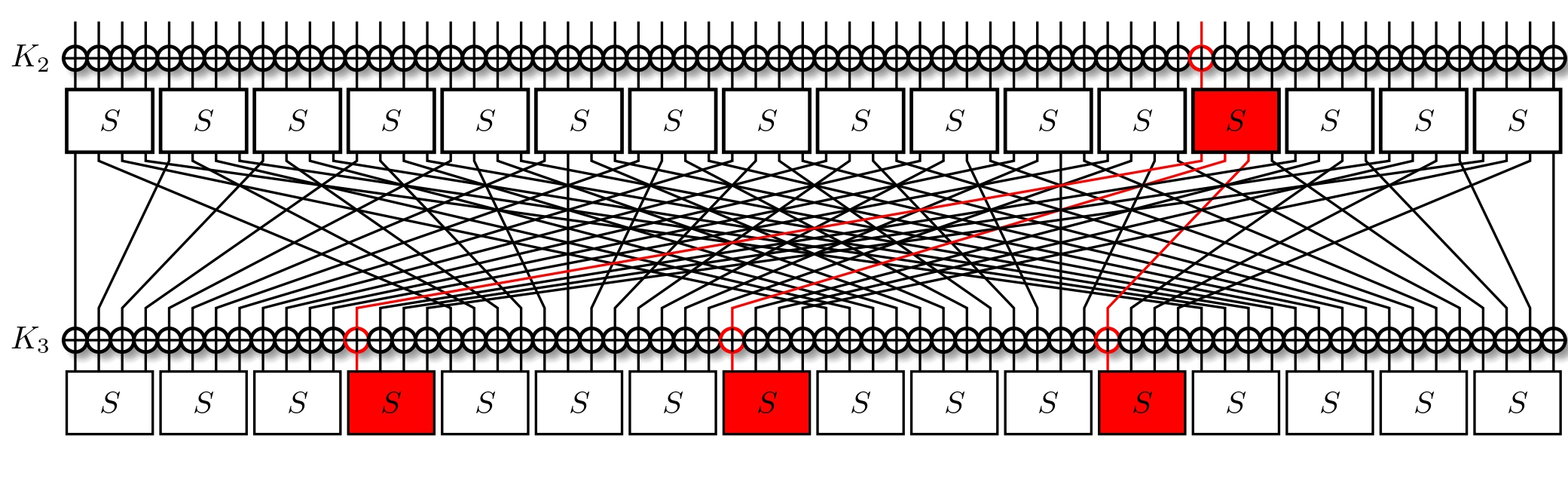

It's important to recall that we're trying to minimise the number of active S-Boxes. This usually means that we're trying to also minimise the number of active bits, all the while maximising the correlation. Taking a look at the LAT, we find that for an input mask of $\text{0x8}$ we've two output masks with a correlation of $2^{-1}$, those being $\text{0xe}$ and $\text{0xf}$. Out of these, the former activates less bits, so we opt for it instead. With three active bits, we trace them through the permutation layer, and now activate three S-Boxes.

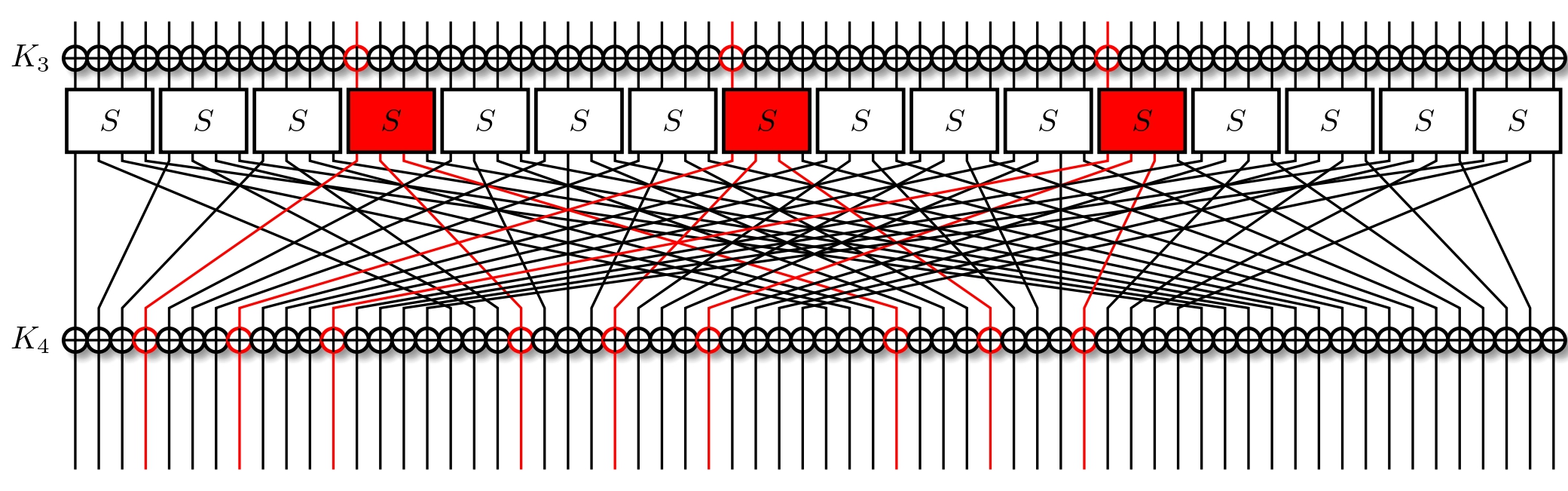

Notice how we have the same input masks in all three S-Boxes? What's more, they're the same that we used for the previous layer. To simplify, we can just reuse our previous approximation, and watch it propagate.

We're interested in the overall correlation. Recall that it's equal to just the product of all of our approximations. So total correlation of above output masks for the initial input mask of $\text{0x3} \ll 60$ is $$ \textbf{corr} = \textbf{corr}_1\textbf{corr}_2 \textbf{corr}_3 $$ equating to $$ \textbf{corr} = 2^{-1}2^{-1}(2^{-1})^{3} = 2^{-5} $$ To notice a correlation $\textbf{corr}$ with a bias $\epsilon$ we need $N$ plaintext-ciphertext pairs, where $N$ is $$ N \approx \frac{1}{\epsilon^2} = \frac{4}{\textbf{corr}^2} $$ Naturally, this can vary for a lot of reasons, but in general we expect it to hold. In our case, we expect to need $N \approx 2^{12}$ pairs to notice the approximation.

Now we collect many plaintext-ciphertext pairs for 4-round PRESENT, and observe whether the XOR of the input bits and output bits is equal.

cipher = Present(key=randbytes(16), rounds=4)

inmask = 0

for i in [0,3]:

inmask ^= 1 << (63-i)

outmask = 0

for i in [3,7,11,19,23,27,35,39,43]:

outmask ^= 1 << (63-i)

pts = []

cts = []

N = 2**12

for _ in range(N):

pt = randbytes(8)

ct = cipher.encrypt(pt)

pts.append(int(pt.hex(),16))

cts.append(int(ct.hex(),16))

Recall that we expect a XOR of random variables to be similar to a random distribution, so it's best to compare these results to one.

def xorsum(value):

xorsum = 0

while value:

xorsum ^= value & 1

value >>= 1

return xorsum

balance = 0

for pt, ct in zip(pts,cts):

res = xorsum(pt & inmask) ^ xorsum(ct & outmask)

if res == 0:

balance += 1

else:

balance -= 1

print("Approx:", balance)

balance = 0

for pt, ct in zip(pts,cts):

res = randint(0, 1)

if res == 0:

balance += 1

else:

balance -= 1

print("Random:", balance)

Truly, when comparing, we do get a noticeable bias in the outputs. It's a bit easier to notice this were we to up the value of $N$ to something like $2^{14}$.

We have a working distinguisher here! For such shorter linear trails, we don't expect many things to go wrong. This is in part due to the limited search space: there's only so many linear trails to find. As trails get more complex, it's possible for different trails to exist for the same input and output masks. This may seem positive, and in the differential case it really is a good thing, but this can also have negative consequences when we have trails of a different sign.

Hull impact

TODO: Find example with hull impact